This is my Policy Brief, the culmination of the 3-month German Marshal Fund’s Comparative Domestic Policy fellowship I spent in Italy and Germany in 2009. This contains a couple of “lessons learned” that got edited out of the Policy Brief on the GMF website, due to the word count limitations. (www.gmfus.org/cdp)

Land Development and Transportation Policies for Transit-Oriented Development in Germany and Italy – Five Case Studies

Across the United States, metropolitan regions are increasingly turning to transit-oriented development (TOD) as a logical alternative to the auto-dependent land development patterns of the last six decades. TOD projects, however, face policy hurdles that could inhibit their effectiveness, particularly those that address land use densities, parking, and the role of traffic impact studies. American planners can benefit from a comparative examination of recent TOD developments in Europe, where transit is taken for granted and land use planning has evolved concurrently.

Evolution of the Policy Causality-Loop Conundrum

American decision-makers are often stymied by how and where to enter the following causality loop:

Mass transit[1] can help reduce traffic congestion. However, mass transit is only tenable with high ridership. High ridership is achieved through denser land use. Yet, unless mass transit service is already in place, density often leads to increased traffic congestion.

Before World War II, most American cities had well-developed transit systems. The transition from transit-based to auto-based urbanized areas was slow but steady. For many reasons, including increased affluence, cheap gasoline, and development of the Interstate Highway System[2], transportation planning gradually became roadway planning and transit planning became an afterthought. This was especially true in the West and in California where it seemed there was an infinite supply of land. Auto-dependency became the norm, and by the 1960’s whole communities were built without any transit since roads and freeways could be forever widened. Consequently, transit service, ubiquitous before 1940, suffered. Although toward the end of the 20th century, transit service improved in many parts of the country, roadway capacity remained the main focus of transportation analyses and investments in most metropolitan areas.

Consensus has finally been reached that roadways can no longer be widened ad infinitem. Traffic congestion was not eliminated even with 12-lane freeways, 6 to 8-lane arterials and double (and triple!) eft-turn lanes. Transit’s role in reducing congestion and providing mobility is now recognized. Yet transit cannot increase ridership without significant geographic expansion and improved service levels. However, transit agencies cannot justify expansion unless it would pay off with more riders. How can we get around this chicken-and-egg conundrum? Transportation planners and transit advocates have realized that the missing element is land use. Ridership will inevitably increase when density is created near mass transit stations. Likewise, denser developments benefit through greater access for customers and increased commuting options for tenants. This symbiosis is transit-oriented development.

TOD brings us to a new location in the causality loop: mass transit needs denser land use but denser land use can overload the immediate area with traffic, especially when it is built without transit infrastructure. Furthermore, the National Environmental Protection Act (NEPA) [3] requires a traffic impact study for most developments. If road widening is not an option, developers are sometimes asked to reduce the size of a project (which of course reduces its density) to mitigate the “traffic impacts”. In addition, local parking ordinances often require parking to be built at the same car-centric ratios regardless of proximity to transit.

Over the past 15 years, California has seen an increasing trend of high-density mixed-use projects both near and far from transit stations, with and without bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure. Generally, the same standards for parking and traffic “impacts” were applied to TOD areas. During my fellowship, I looked at how European planners made crucial decisions regarding land use density, parking, and traffic studies in the planning and approval of land-development projects. I studied projects in five Italian and German cities to identify lessons for American policies and practices in TOD.

I studied projects in Turin, Milan and Genoa, Italy and in Stuttgart and Hamburg, Germany. [4] All case studies were located within city limits at a mass transit station: commuter rail in Hamburg and Genoa; light rail / tram stations in Stuttgart, Turin, and Milan; and a metro station in Milan and Turin. All were built (or had components built) since 2000 and are occupied, with the exception of the Milan project, currently under construction.

Turin, home to Fiat, and Stuttgart, home to Mercedes–Benz and Porsche, are relatively auto-dependent as reflected in their auto-ownership rates shown in Figure 1. Genoa and Hamburg are major seaports with many port-related industries. The fifth city, Milan, also has a large industrial base. In general, none of the cities is known for being particularly innovative or aggressive in discouraging car use. Therefore, their policies may be more transferable to car-centric American cities than those of other European cities.

Lessons Learned from Italy and Germany

For each case study, I interviewed city planners, architects and engineers about the process for determining land use mix and densities as well as parking and traffic study requirements. I identified many lessons for American practitioners. The lessons below reference their applicability primarily to San Francisco Bay Area projects, but can potentially be applied to other metro areas as well.

1. Mass transit is essential to a livable city.

My research of TOD projects was not specifically about transit service, yet the transit setting in Italy and Germany cannot be ignored. All five case studies had at least two forms of mass transit[5] with excellent  coverage throughout the entire urban area. The commitment to provide and fund both mass transit and local bus service was so ingrained that it is considered one of the essential components of a livable city, along with clean water, sanitation, and garbage collection. In short, frequent, affordable, and fast mass transit enables hundreds of thousands to live in dense urban areas; it is accepted that the government will provide (or contract for) transit service.

coverage throughout the entire urban area. The commitment to provide and fund both mass transit and local bus service was so ingrained that it is considered one of the essential components of a livable city, along with clean water, sanitation, and garbage collection. In short, frequent, affordable, and fast mass transit enables hundreds of thousands to live in dense urban areas; it is accepted that the government will provide (or contract for) transit service.

2. Density and mass transit must be planned in concert.

Mass transit needs density and density (and society) benefits from mass transit. Allowing high densities where there is no mass transit is as shortsighted as allowing low densities at mass transit stations. Long-range transit planning is essential. This can be as visionary and pro-active as 1920s Hamburg constructing five commuter rail lines and preserving adjacent land for future infill development, or late 20th century catch-up projects such as Turin opening its metro line in 2006.

Furthermore mass transit must be an integral part of every development project. Of all my case studies, the underlying assumption was that if a large project was being developed, then the train, metro, or tram would be extended to serve it. This will only work if there is a train, metro, or tram to extend.

In Santa Clara County, the proposed Coyote Valley project in south San Jose is located along the Caltrain commuter rail line; a new station is planned to serve the site. In Oakland, however, the largest redevelopment opportunity is the former Oakland Army base; the only mass transit line (BART) is over one mile away. Although BRT is in the planning stages, it is not currently planned to serve this site. Since the base redevelopment project is on hold, it is hard to criticize the lack of planning for BRT. But when the project is revived, the City of Oakland should ensure that it indeed has mass transit so that the mistakes of the past fifty years are avoided.

3. Density Should Not Be Feared or Avoided

In both Italy and Germany, density and land use are decided by assessing the surrounding area to determine the new site’s density. The proposed land-use mix then undergoes a public process to determine what land uses/services are missing from the neighborhood. While cities are expected to have more multistory buildings than the suburbs, density is not uniform throughout the city; it varies based on factors such as topography and transportation infrastructure. The two cities that chose more dense development, Stuttgart and Milan, based decisions on proximity to major transit stations. Two cities justified the same densities for the same reason. One city made the decision that the site should be less dense due to the neighborhood’s lack of open space. (However it must be noted that this “less dense” development was the equivalent of 63 dwelling units (d.u.) per acre; for comparison, San Jose’s highest residential density zoning is 20-50 d.u./acre.)

The most significant influence on density was proximity to transit. It is accepted practice in both Italy and Germany that denser developments must be closer to mass transit. Surprisingly, this key TOD practice was not officially adopted policy.

4. Parking Requirements cannot be “One Size Fits All”

Parking supply regulation is one area where U.S. policies appear more effective than in Italy or Germany. German and Italian cities must comply with nationally mandated overly high parking requirements.  Typically in the U.S., each city has the flexibility to set parking requirements for new development. However, local control does not always result in effective parking policies; each city must independently recognize the impacts of overly strict parking standards and change its ordinances. For instance, Italian and German cities are required to provide bicycle parking, in contrast to the city-by-city ordinances in the U.S. that often fail to address this need.

Typically in the U.S., each city has the flexibility to set parking requirements for new development. However, local control does not always result in effective parking policies; each city must independently recognize the impacts of overly strict parking standards and change its ordinances. For instance, Italian and German cities are required to provide bicycle parking, in contrast to the city-by-city ordinances in the U.S. that often fail to address this need.

In sum, context is important: one size does not fit all cities or all neighborhoods. Both Turin and Milan have realized that national parking standards are too high for land uses next to mass transit. The state of Baden-Württemburg, where Stuttgart is located, has adopted, and the City of Milan is about to adopt, lower parking ratios for office/retail developments located near mass transit. The developer funds that would have built parking are now used for other City services; the developer doesn’t benefit from building less parking – the public does.

5. Developer fees for transportation impacts should be based on a set formula applied equally across the metropolitan area rather than on a case-by-case basis.

Italy and Germany have standard development fees for public works projects, and Italy also has fees to improve the public space (in addition to land donation). In California, traffic impact fees are often determined through project-specific traffic studies, a method which benefits those projects developed first, when roadways could still absorb the traffic. It also encourages suburban sprawl. Thus, many California communities have implemented or are considering traffic impact development fees or ways to allocate costs proportionately to fund future transportation improvements. However, improvement projects are typically roadway projects; impact fees to fund transit capital or operating costs are rare. Improvements are almost always confined to one city; regional cooperation is extremely difficult. Finally, travel forecasting models used to predict future traffic volumes and future roadway needs are calibrated on historical trip-making patterns, which are the result of auto-dependent land use.

Standard fees citywide would be more equitable than project-by-project, but region-wide fees, which would keep developers from playing one city against another to obtain the lowest fees, would be even better.

6. Mixed land use is a component of a successful project.

All five of my case studies were part of a mixed-use project, which included at a minimum residential, office space, retail and at least one other land use. In some cases the residential buildings were themselves mixed use, in that they incorporated ground-floor retail and office; in other cases the land uses were segregated into separate buildings. Nevertheless, the case studies showed that an area as small as 12 acres benefits from the synergy of varying land uses and even varying residential uses (including student housing in Turin and Stuttgart, and owner-occupied row houses in Hamburg).

7. Vibrant cities will have traffic congestion

While traffic studies were conducted at various stages, traffic impacts did not affect, let alone rule, the density decision. Furthermore, a good mass transit system enables the construction of high density developments without having to “mitigate” traffic congestion. As Milan’s CityLife project forecast, drivers will pay the price by waiting in traffic, but the metro riders will be unaffected. Building more freeways and roadways is a vicious cycle; if there is anything that California has learned in the last 50 years, it is that “if you build it (freeways and wider roadways), they (motorists) will come”.

Case Study: Turin

The major transportation project in Turin for the past decade has been Spina Centrale- the Central Spine – a 12-km corridor that contains the new metro, and which includes undergrounding the railways that provide commuter, regional and intercity train service. It also includes a complete redesign of Corso Inghilterra, the former industrial frontage road to the railroad tracks. This project has made 2 million m2 (500 acres) of land available for redevelopment. The city divided this large corridor into four project areas called Spina 1, 2, 3, and 4. This case study focuses on the site within Spina 2 called “Spina 2-PRIN,” directly served by two tram lines and 300 meters away from the existing Porta Susa train/metro station.

Land use and density for this project was determined by the city’s General Plan (PRG[6]). The PRG specifies the Floor Area Ratio (FAR, the ratio of building floor area to parcel size,)[7] and the land use mix for each building. Critically, Italy has a national law requiring a significant percentage of the property be donated to the city for public facilities. A strict formula allocates the donation into four categories, one of which is public parking. [8] This law in effect increases the density on an individual parcel since the allowable building size is now built on a smaller land area.

The plan was for Spina 2 to blend in with the existing neighborhood in terms of land use, density, and the street network, but with more public space; therefore the maximum allowable FAR was 0.7. The PRG also required that the buildings have both residential (60% — 80%) and retail/office (40% — 20%). In the U.S., housing densities are typically described in terms of the number of dwelling units per acre; requiring mixed use within a residential building is still uncommon.

In the case of the 12.7-acre Spina 2-PRIN, 4.1 acres were developed by the developer and 8.6 acres were donated to the city. The allowable building area was 37,000 m2 (70% of 12.7 acres ) but in fact only 31,000 m2 was built: 260 apartments in three multistory buildings with a total of 2,300 m2 retail and 5,000 m2 office. From an American perspective, this comes to 20 d.u./acre over the full 12.7-acre site, or 64 d.u./acre on the 4.1 acre parcel. Given that these buildings also contain office and retail, the net use is even higher, equivalent to over 80 d.u./acre.

Parking: Parking is calculated using formulae set by the national government for both “private” and “public” parking. New projects in areas that are already “built” need only provide 50% of the parking specified for “expansion zones.” Cities and regional governments may increase parking supply, but only regions may decrease nonresidential parking. Residential buildings must supply approximately one parking space per residential unit, and 2.5 m2 per inhabitant for public parking. This public parking is part of the land donation required for “public facilities”.

Public parking may also be provided offsite. In Spina 2-PRIN, the public parking location is still being evaluated together with that required by the rest of Spina 2 and Spina 3, so its construction has been deferred to the next phase of redevelopment.

Turin’s parking rates have not changed since 1977, and adhere to regional and national standards, set in 1968. As planning continues for the remainder of Spina 2, it is apparent that the current one-size-fits-all parking requirement will be extremely expensive to provide. Given its proximity to Turin’s main transit hub, city planners are recognizing the inefficiencies of spending hundreds of millions of Euros on transit improvements only to require parking at the same ratios as before.

Traffic Studies: While studies were conducted of future transportation conditions based on the redevelopment, increased railway capacity, new metro line, and new boulevard atop the undergrounded rail, there was no “traffic study “ of Spina 2-PRIN alone. The boulevard serving the project was designed with four-lanes, wide medians, sidewalks, and bike paths based on the city’s desire for aesthetics and the needs of all users; not based on a series of traffic level-of-service (LOS) calculations, as is standard practice in California and much of the U.S.

Finally, development fees for transportation are not determined based on the project’s traffic impacts, but on formulas developed by the city and state for all developments.

Milan

Milan’s old fairgrounds occupied a large site, about 0.6 kilometers km2 (over 100 acres) in a central location less than 3.5 km from the Duomo and the central train station. Given its prime location, Milan decided the site was better suited for a mixed-use development,[9] and held a competition for proposed designs. The winning project is called “City Life.”

Density: To build City Life, Milan amended its zoning plan to change the use from fairgrounds to mixed use, allowing an FAR of 1.0., under the premise was that it be denser than surrounding areas, but would offer more parks and open space. This density-open space combination was accomplished by concentrating residential uses in three 27-story towers. Another key decision was not to extend roadways through the project site; rather it is designed as a campus with pedestrian and bicycle pathways and all parking underground. Non-residential buildings, including a museum, retail and offices, were determined through public meetings and negotiations between the city and developers.

The three residential buildings each have 500 d.u. and total 148,000 m2 of floor area on 36 acres, equivalent to 41 d.u./acre. 55% of this land area (19 acres) will be donated to the public, creating a net density of 85 d.u./acre.

Parking: City Life was approved using national parking formulae for residential parking and the Lombardia region formulae for public parking. Parking for office alone requires 1 m2 of parking per 1 m2 gross floor area. In total, about 4,000 public parking spaces were required. Coincidentally, a new metro line had been sited near the project. City planners realigned the metro and sited a new station underneath City Life, and then re-analyzed the project’s traffic and parking generation, concluding that parking could be drastically reduced to 1,000 spaces. The funds that the developer would otherwise have spent on parking will be paid to the city for other public services.

Traffic Studies: Traffic studies for City Life concluded there would be significant congestion on one of the main access roads and recommended that it be undergrounded directly into the project’s parking garage. Milan planned to use the € 60 million in development fees to fund this tunnel, but the community and neighbors objected since these fees are intended to benefit the entire neighborhood, and they deemed the underpass would only “benefit” the project’s tenants and customers. Thus, it will not be built at this time because it lacks funding. Currently, metro and other public transportation provide alternatives to driving.

Genoa

In Genoa, the “Fiumara” site previously housed several factories near the coast and port. In 1989, the city adopted a new general plan for the redevelopment of this and other sites to reflect the changing economy. Fiumara is not served by the (5.5 km) metro, but is directly served by a train service called “linea metropolitana.” It runs several times an hour and is equivalent to commuter rail. By walking to the end of the platform, one can take stairs directly into the Fiumara campus.

In Genoa, the “Fiumara” site previously housed several factories near the coast and port. In 1989, the city adopted a new general plan for the redevelopment of this and other sites to reflect the changing economy. Fiumara is not served by the (5.5 km) metro, but is directly served by a train service called “linea metropolitana.” It runs several times an hour and is equivalent to commuter rail. By walking to the end of the platform, one can take stairs directly into the Fiumara campus.

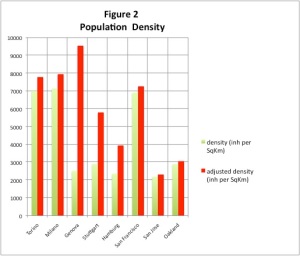

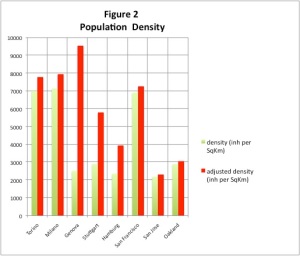

Density: Genoa worked with the neighborhoods to select land uses that were under-represented, particularly public recreation. Fiumara has a movie theatre complex and a multisport fitness center in addition to the typical housing, retail, and office buildings. Genoa’s steep terrain concentrates the urbanized area on 64 of the city’s 240 km2. Thus, Genoa is one of the densest cities in Italy (and the densest case study, as shown in Figure 2); significant open space was therefore considered essential.

Population Density Comparison

To maximize open space, city planners concentrated housing in three 19-story towers; built few roads within Fiumara, netting more land for green space and less for pavement and roadways; and like Milan’s City Life, designed roadways to go directly into the parking garage.

Aiming for less density compared to the surrounding  neighborhood, Genoa’s zoning plan was amended to allow 0.7 FAR. The resulting 270 d.u. on 9.2 acres is 29 d.u./acre. Adjusted for the land donation to the public, the net density is 63 d.u./acre.

neighborhood, Genoa’s zoning plan was amended to allow 0.7 FAR. The resulting 270 d.u. on 9.2 acres is 29 d.u./acre. Adjusted for the land donation to the public, the net density is 63 d.u./acre.

Parking: Parking in Genoa has always been at a premium, and as redevelopment has been so rare, very little of the city’s land use meets the national standards for “existing,” let alone expansion, sites. No attempts were made to reduce parking, as in Milan, or delay building it, as in Turin, since in Genoa very little street and off-street public parking exists, compared to other cities.[10] Genoa required all public parking for Fiumara be concentrated in one five-story parking garage. Private parking for residential and offices is underneath each building.

Stuttgart

Stuttgart’s Möhringen Station was historically a freight station and rail yard. As the city built its tram lines, the station became important in linking the former village of Möhringen to the city center. Eventually the rail yard became defunct and in 1995 Stuttgart began to plan for its redevelopment.

Density: Since Stuttgart’s latest general plan was from 1990, an amendment was needed for the Möhringen station area. Planners considered its location at a light rail station, and the services required, including a supermarket, a kindergarten, senior residences, and student housing. Stuttgart selected densities consistent with other city areas with these same characteristics, even though Möhringen was much denser than the adjacent neighborhood. Furthermore in the zoning amendment, the city rezoned the abutting low density housing to this same higher density.

Land use density in Germany is set by two parameters: the FAR, and the maximum building footprint ratio (GRZ in German). The Möhringen apartments’ footprint was set at 60% maximum and the FAR was 1.8. For the main residential buildings, the land use mix was required to be 80% residential and 20% retail/office. The five residential buildings have four stories with 36 d.u. each and ground floor office/ retail. This calculates to 42 d.u./acre.

Parking: Parking standards in Germany are set by the state, in this case the state of Baden-Württemburg, which mandates 0.8 space per unit of multifamily housing; no public parking is required. For nonresidential uses, the formula gets quite complicated depending on the specific type of retail permitted. This supply is then divided into public versus private. Stuttgart sets additional parking conditions on a project-by-project basis. In the case of Möhringen’s residential buildings, virtually all parking had to be underground; three handicapped spaces per building were allowed at-grade. Public parking for visitors and shoppers is only available on the street.

Traffic Studies: Traffic studies and an EIR were performed but do not affect the density or the development fees, which are based on a formula, and appears to be less than Italy (especially considering the required land donations in Italy). Since more housing is desired by the city of Stuttgart, residential development is encouraged and thus is subject to fewer fees compared to other land uses.

Hamburg

Hamburg, the largest city studied, is both a city and a state, and therefore has more autonomy in setting development and parking regulations. In the 1920s, Hamburg built a radial system of commuter lines in addition to an urban metro system. Over the years, Hamburg bought land near the commuter tracks to preserve for future residential uses. In the late 1980,s planning began for one of these areas, known as Allermöhe. A new train station was built to serve the planned population of 12,000. The total site includes retail, apartments, lower density townhouses, four schools and other community uses. In 1995, the first residents arrived ; a few undeveloped parcels remain.

Allermöhe is essentially a stand-alone development since it is not contiguous with an existing developed area of the city, and resembles a California-style “subdivision” project, with four key differences:

1) Deliberately sited next to a commuter rail line and a new train station built for the  development;

development;

2) Includes a mix of uses (retail, office, community center, sport fields, schools from daycare through high school);

3) Two distinct styles of homes, for socio-economic and demographic diversity; and

4) Designed to make it easier to walk rather than drive to the train station and shops. Canals that help with flood control and offer recreational opportunities are also effectively used to facilitate bike and pedestrian circulation, although car access to the shops and between homes is possible.

Density: Allermöhe is sandwiched between a railroad line and a freeway, and surrounding land uses will remain agricultural. Land use densities were similar to Bergedorf, an established community at the next train station. City planners also based decisions on lessons learned from 1 970s development, rejecting high-rise residential buildings in favor of three and four-story apartment buildings to enhance the sense of community. Density for the apartments was set to 0.4 GRZ / 1.2 FAR, whereas townhome density was set at 0.4 GRZ / 0.8 FAR. This translates into 61 d.u. / acre and 23 d.u./acre, respectively. Schools and retail areas were allowed higher building footprints.

970s development, rejecting high-rise residential buildings in favor of three and four-story apartment buildings to enhance the sense of community. Density for the apartments was set to 0.4 GRZ / 1.2 FAR, whereas townhome density was set at 0.4 GRZ / 0.8 FAR. This translates into 61 d.u. / acre and 23 d.u./acre, respectively. Schools and retail areas were allowed higher building footprints.

Parking: Hamburg has the most local control of parking requirements of all the case studies because it is both a city and a state. Although within the city center, required parking is 25 % of the city formula, in Allermöhe, the full parking ratio was required: 0.8 space per apartment and 1.0 space per townhouse.

Traffic Studies: An EIR was conducted for the project but the main concern was mitigation of noise from the adjacent freeway. Traffic was not an issue; it was estimated that internal traffic would be low and that external trips would utilize the freeway or the train.

Conclusion

Many areas of the U.S. will continue to experience population growth, primarily concentrated in metropolitan areas composed of several, if not dozens, of different political jurisdictions, not to mention transit agencies. While some cities have gotten the message with respect to density, many of these projects were built far from existing mass transit stations (e.g. Santana Row in San Jose and Bay Street in Emeryville, CA). However it is hard to find fault when there is a paucity of high-capacity transit systems and no long-range plan of where such routes might be.

To guide TOD, a bold new approach is needed to answer the question of what comes first – transit or density. The solution? Region-wide master planning for mass transit networks without regard to political boundaries. Just as in 1956, when the federal government committed to funding the Interstate System[11], the United States needs a similar visionary commitment to plan, construct, and operate efficient, affordable mass transit systems in every urban area as small as 200,000 residents. It should be possible to traverse the metropolitan area via one or more mass transit modes without regard to artificial boundaries, just as we can hop on an Interstate and drive unaware of city and county boundaries. The larger the urban area, the more modes and lines per mode are needed. [12] Identification of these future mass transit routes would provide the needed framework on which local governments would then base their land use zoning plans.

Clearly leadership and coordination at the state and federal levels are needed. Successful models in the U.S. exist for region-wide transit: New York’s MTA, Trimet in the Portland, OR region, and the newly formed transit board in Greater Atlanta. European cities have had a regional perspective for decades: state governments ensure interurban options such as commuter and regional rail, while cities cooperate with their suburbs on where and how to extend metros and LRT beyond city limits. Fare reciprocity is standard procedure between transit service providers within an urban area; this, along with schedule coordination, is an essential component of effective region-wide transit.

This approach could be the needed catalyst to free development impact studies from their focus on intersection LOS. Transportation impact studies, while still necessary, could concentrate on multimodal solutions. Development fees and savings from reduced parking should be set aside to pay for regional transit’s capital and operating costs. Now that the United States has a world-class interstate system, it is time to catch up with rest of the world by providing high quality mass transit in all of our metropolitan areas.

[1] Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), Light Rail (LRT), subways, and commuter rail are collectively referred to here as “mass transit”, to differentiate them from local bus service.

[2] Established in 1944, funded in 1952 and expanded in 1956, the Interstate Highway System was completed after 35 years and cost $114 billion, equivalent to $425 billion in 2006 dollars.

[3] In California, the pertinent regulation is the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA)

[4] Italy and Germany are similar in size and structure: Italy (pop. 60 million) has 20 states called “regione;” Germany (pop. 82 million) has 16 states called “bundesland”.

[5] This is in addition to regional train service provided by the state and interurban rail service provided by the national railway.

[6] Piano Regolatore Generale

[7] FAR is the number of square meters of building floor space per square meter of land area

[8] The other three categories are parks, green spaces and places for sport; education and childcare facilities; and “facilities for the public interest”.

[9] The fairgrounds were relocated beyond the terminus of an existing metro line which was extended to serve the new site; Europe’s Expo 2010 will take place there..

[10] I suspect the reason for the high motorcycle /motor scooter use in Genoa compared to the other case study cities, as shown in Figure 1, has more to do with limited parking supply than traffic conditions or gasoline prices.

[11] Another unprecedented and visionary public project was the State of California’s 1960 Master Plan for Higher Education, which among other things, established tuition-free community (2-year) colleges for all California residents.

[12] A note about the SF Bay Area where I live and work: the City and County of San Francisco is well-served by multiple rail modes, but at 49 sq. miles and 800,000 residents, this is only 1% of the land and 11% of the population of the metropolitan area. San Jose is the most populous city, almost 1,000,000; portions have both commuter rail and light rail, but much of the city has neither. While Alameda and Contra Costa Counties have BART lines, BART is functionally a commuter-train; these two counties have no metro or light rail. To fill these gaps, BRT planning is underway in San Francisco, Alameda and Santa Clara; however it suffers from typical American transit planning limitations: short-range vision due to chronic budget crises endured by American transit agencies. This situation is exacerbated by the current recession and budget crises faced by many states including California. The current emphasis on jobs creation should recognized that transit operations and construction create jobs just as building roads does. In the 2009 American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA), only 17 % of the transportation funding was for transit